Chris’ note: Our offices are closed today for Good Friday. So instead of our usual markets fare, you’ll hear from my old friend Will Bonner about a different subject altogether.

Will and I used to work together in Buenos Aires, Argentina, at a newsletter business there. These days, he runs a wine club. It gives folks access to wines from remote parts of the world – including Gualfin, his family’s ranch high in the Andes in northwestern Argentina.

So if you’re interested in hard-to-get wines, you can become a member of Will’s club here. The wines were a hit at the tastings he hosted at the Legacy Investment Summit in Washington, D.C., a couple weeks ago.

Bringing you wines from remote parts of Argentina isn’t easy. Many of them come from gaucho country. And as Will explains below, gauchos – or Argentine cowboys – are a tough bunch…

It was late in the afternoon when the gaucho spotted the cow.

He steadied his horse and raised his hand, signaling to his cumpas (buddies) that they should fall back and be quiet.

“Beautiful hide,” he thought.

For a moment, he fancied he might keep it for himself. But then he thought of the gold he’d get from the smugglers back in Buenos Aires. That kind of loot could buy a lot of wine.

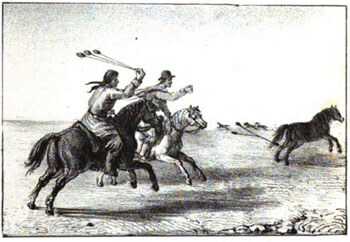

He flung the front of his poncho back over his right shoulder, revealing a coil of rawhide rope with three compact round weights at the ends – his boleadoras.

He swung the boleadoras over his head, heard them whir through the air, then let them fly.

They hit their mark.

Later, the gaucho and his cumpas prepared the cow for skinning with their cuchillos – long, razor-sharp knives that every gaucho wears on his belt.

Suddenly, one of the gang let out a pssscht (it was halfway between a “psst” and a whistle), signaling the others to look up.

A pair of horsemen stood on a ridge overlooking the scene. From their clothes, the gaucho could tell they were Portuguese… likely rawhide smugglers headed north.

The gaucho and his cumpas stood, wiping their bloody knives to let the steel sparkle in the sun.

A Portuguese never attacked a gaucho with an unsheathed cuchillo.

Sure enough, the riders turned away…

The American cowboy has his lasso, six-gun, and Stetson hat.

The Argentine gaucho has his boleadoras, cuchillo, and wool poncho.

And a good gaucho never misses a chance to partake in a traditional asado (barbecue), with ultra-tender steak and a bottle of malbec. (Can’t go wrong with an extreme-altitude malbec over 200 years in the making…)

This projectile weapon came from the bolas (ball weapons) indigenous tribes throughout the Americas used.

Originally, it was a piece of rope with weights attached to the ends.

When a gaucho threw the device at an animal, the weighted rope wrapped around the animal’s legs. This tripped it up and stopped it from rising back up.

The boleadoras is made of tough rawhide. It improved on the bolas design with heavier, rounded weights – stone wrapped in bull scrotum – and the addition of a third weight. The third weight is lighter than the other two and is attached to a slightly lighter and longer piece of rope.

Throwing the boleadoras from horseback. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The heavier weights take the legs out from under the animal. The third entangles them.

This was a necessary increase in firepower for hunting the wild cattle and horses that once roamed the Pampas – or lowlands – outside Buenos Aires.

Boleadoras made of rawhide from cattle or wild horse with weights wrapped in bull scrotum. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Along with wild cattle, the boleadoras was a fearsome weapon for taking down people (it could also be used as a flail in close combat) as well as the rhea. This South American ostrich is a large flightless bird from Argentina’s grasslands. People hunt it for its meat and plumage.

When enormous herds of wild cattle and horses roamed the vast grasslands of the Pampas, the Spanish crown imposed a monopoly on the trade in animal hides from Argentina (which was then part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata).

But the Pampas – an area larger than the state of Texas – proved hard to police. And a lively smuggling trade sprang up.

Two rival groups, Portuguese gangs (who came down from what’s now Brazil) and Argentine gauchos, dominated this trade.

In the early days of the trade, the Portuguese were reportedly surprised when gauchos challenged them wielding not swords or guns, but what appeared to be large carving knives.

In time, they’d have a healthy respect for the damage a gaucho and his weapon could do, especially at close quarters.

A gaucho with his cuchillo tucked into his belt. Source: Wikimedia Commons

There are various names for the gaucho blade.

It’s not quite a dagger. And it’s too small to be a sword.

The most common name in the northwestern desert is cuchillo. Other names are facón, daga, and puñal.

The cuchillo was the gaucho’s most versatile tool. It could kill, butcher, and skin. It was also the gaucho’s sole utensil for dining outside on the range (gaucho diets were mostly meat).

Nineteenth-century Argentine president Domingo Sarmiento wrote of the gaucho and his cuchillo:

The knife, more than just a weapon, is an instrument that serves him in all his work. He can’t live without it; it is like an elephant’s trunk, his arm, his hand, his finger, his everything.

Various forms exist. But the cuchillo most commonly resembles a butcher’s knife with a longer, narrower blade and a bone handle. Owners commonly keep it in a leather or silver sheath.

A cuchillo in a silver sheath, tucked into a leather belt. Source: Getty Images/iStockphoto

The gauchos didn’t use guns.

In the early days, guns were rare on the vast, lonely Pampas. Large-scale commercial production of guns – such as the Remington repeater or the Colt revolver – had not yet begun. What rifles existed were expensive and prone to mishap.

The gauchos grew to condemn guns as unreliable tools for cowards too afraid to handle knives.

American cowboys favored the leather duster in the 19th century. But despite a huge leather industry, this never took off down in Argentina.

For the gaucho, it would’ve been hard to argue that a heavy coat of stiff leather improved upon a warm, waterproof poncho.

The poncho was widespread by the time the Spanish showed up in South America. It likely originated either in the high desert of Peru or the mountains of Ecuador – climates where a tightly woven sheet of alpaca wool could be a life-saving shield from the volatile elements.

A poncho might have been the gaucho’s most valuable possession besides his horse (and a good bottle of Malbec). Out on the range, where he was a lone figure under a vast sky, the poncho was his shield, his coat, and his bed.

We’ve been out with gauchos a time or two on the high desert plains of the Calchaquí Valley. We brought our sub-zero sleeping bags and mats. The gaucho threw down his saddle bags next to the smoldering coals of the open fire and curled up under his poncho and a saddle blanket.

The classic red and black wool poncho. Source: Wikimedia Commons

At the turn of the 20th century, railways and fences came to the Pampas. Ranchers brought domesticated cattle (or fenced in whatever wild herds happened to be on their land). Guns replaced boleadoras and cuchillos.

But in the most remote corners of Argentina – Patagonia and the pre-Andean plateau (like the Calchaquí Valley) – the gaucho still rides.

Nos vemos (see you later),

|

Will Bonner

Founder, Bonner Private Wine Partnership

P.S. If you’re interested in a taste of gaucho living, we can’t ship boleadoras to your doorstep… but you can reserve a special collection of “gaucho wine” from the extreme altitudes of the Calchaquí Valley.

No shipping delays, no inflated prices, no middlemen. Simply click here to experience the Calchaquí Valley for yourself.